“Gambling in the Movies” is a new blog series at the CGR in which we will revisit some essential gambling movies, and discuss their portrayal of gambling, gamblers and games of chance. If any readers have recommendations for films, then please let us know!

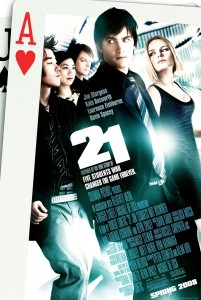

Having been given the first choice of gambling flicks, I chose the venerable champion of new-millennium gambling movies, Robert Luketic’s “21” (which also happened to be my first date-movie as a teenager). Released in 2008, 21 is an adaptation of “Bringing Down the House,” by Ben Merzrich. Starring Jim Sturgess and Kevin Spacey, the film tells the story of Ben (Sturgess), a bright MIT undergrad who, trying to pay for Harvard Med, joins a group of students led by Professor Rosa (Spacey). After each week of classes, the team flies to Vegas to wager, and win, millions by using a card-counting blackjack strategy.

Blackjack is one of a small handful of casino games in which the player can, by using different strategies, improve their odds of winning. In blackjack, card counting allows the gambler to adjust their bet at points in play where desirable cards are over-represented among the cards yet to be dealt from the deck. As the number of low-value cards drawn increases, and as the number of cards remaining in the deck decreases, the likelihood of drawing a high-value card becomes more certain and the chance of hitting close to 21 improves

.

Card counting is central to the plot of 21, but we felt that the film misrepresents its utility. First, the movie asserts that “simple math” in the form of card counting is all that is needed to give the player an advantage over the house. To the dismay of many would-be card counters, most casinos employ a number of practices to make sure that counting is an unreliable strategy, maintaining the house advantage. One method that has become common practice in the time since Merzrich’s book is simply switching to a new deck of cards well before the current deck runs out, which makes card counting more unreliable.

Equally troubling is the length that the film goes to portray card counting as a flawless strategy. In every scene where the main characters are playing by their counting system, they have winning cards. At no point is card counting shown to result in a losing hand. This is an unrealistic representation of the way card counting works. Suppose that you were at a considerable advantage, 55%, against the house. It is still expected that, hand-to-hand, you will be losing your bet nine out of every twenty hands. The nature of card counting is such that the statistical advantage causes winnings to accumulate in proportion to the bet amount as the counter plays many, many hands. Stranger still is the way 21 presents losing hands. Every losing hand played by the main cast is directly related to some personal failing: being drunk, emotionally distraught or otherwise “out of control.” In this way, 21 portrays gambling as an activity where smart, rational people win big and emotional, erratic people always lose.

In spite of all this, we at the CGR had a lot of fun watching 21! To close simply, 21 is a fun movie. If you recognize that winning at blackjack is much more than just mastering “simple math,” and that even the best systems are bound to lose regularly, then I think you’re in for a good time with 21.

Our average rating of 21:

Enjoyableness: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fair portrayal of gambling: ![]()

![]()

![]()

Look out for our next gambling movie review, “Kung Fu Mahjong,” chosen by Stephanie.

About the author: Spencer Murch is a first-year Masters student at the Centre for Gambling Research at UBC.