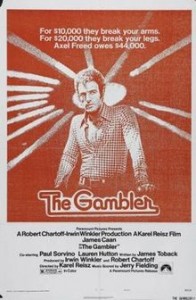

After a short hiatus, the CGR film series is back with an old-school classic. The Gambler has been recently remade featuring Mark Wahlberg, but we wanted to take on the 1974 original, written by James Toback (a problem gambler) and starring James Caan (who at the time was struggling with cocaine use). As a couple of us had already seen the remake, we were also interested in the changing cinematic portrayal of gambling addiction over the space of four decades. Caan plays Alex Freed, an English literature professor who is lectures are inspired by Dostoevsky’s obsessions with gambling and fate, and who enters his own downward spiral to becoming a “degenerate gambler.” In the opening sequence, Freed loses $44,000 playing table games. He convinces his mother to bail him out, but promptly gambles with the loan instead of securing his safety. Taking his girlfriend on a trip to Vegas, he starts to win, but as he returns to New York, with his bookmaker becoming increasingly threatening, Freed’s continual loss chasing only gets him deeper in trouble. After losing his last funds on sports betting, his bookmaker’s bosses force him to persuade one of his students, a star basketball player on the college team, to throw their next match. Throughout his descent, Freed’s lack of insight and emotional detachment from the gravity of the situation, is one of cinema’s best depictions of the gambling addict.

After a short hiatus, the CGR film series is back with an old-school classic. The Gambler has been recently remade featuring Mark Wahlberg, but we wanted to take on the 1974 original, written by James Toback (a problem gambler) and starring James Caan (who at the time was struggling with cocaine use). As a couple of us had already seen the remake, we were also interested in the changing cinematic portrayal of gambling addiction over the space of four decades. Caan plays Alex Freed, an English literature professor who is lectures are inspired by Dostoevsky’s obsessions with gambling and fate, and who enters his own downward spiral to becoming a “degenerate gambler.” In the opening sequence, Freed loses $44,000 playing table games. He convinces his mother to bail him out, but promptly gambles with the loan instead of securing his safety. Taking his girlfriend on a trip to Vegas, he starts to win, but as he returns to New York, with his bookmaker becoming increasingly threatening, Freed’s continual loss chasing only gets him deeper in trouble. After losing his last funds on sports betting, his bookmaker’s bosses force him to persuade one of his students, a star basketball player on the college team, to throw their next match. Throughout his descent, Freed’s lack of insight and emotional detachment from the gravity of the situation, is one of cinema’s best depictions of the gambling addict.

The 1974 story has much overlap with Rupert Wyatt’s 2014 remake. The stories’ core elements are effectively the same, although James Caan and Mark Wahlberg channel slightly different takes on the problematic gambler. The original film’s Freed is a rawer and more candid portrayal of gambling addiction. Wahlberg’s Jim Bennett exudes a more sophisticated and suave demeanor. The two movies also depart drastically in their resolution of the protagonist’s journey. In the remake, Wahlberg’s character walks away from his obsession with little apparent effort, in what might be considered either naïve or borderline irresponsible in portraying problem gambling. But the 1974 original refuses to satisfy the viewer with such an upbeat ending; as Freed leaves the basketball match on a high, he gets into an altercation with prostitute, in which he challenges her pimp to kill him, effectively betting his own life. Escaping the scene with only a brutal cut to his face, Freed looks in mirror and smiles.

The film stimulated much debate in the lab about the relationship between the plot, and traditional theories of problem gambling. The film’s climax is consistent with a psychodynamic account of gambling from the 1950s, that the gambler is driven by a masochistic desire to lose as a form of self-punishment. Elsewhere, however, the film preempts later cognitive theories of gambling, which emphasize the gambler’s beliefs in their capacity to win. Indeed, in this regard, the film presents a more nuanced account of problem gambling that the much later classic Owning Mahowny, the latter film being largely silent on Mahowny’s motives or thoughts about the game. Freed describes a variety of cognitive distortions involving his luck and skill. Most prominent is that of the ‘hot hand’: Freed states that he is blessed, and he cannot understand how he lost $45,000 on three sports bets when he was on an exceptional winning streak the same evening.

It is worth noting that the film predates the medical recognition of pathological gambling in 1980, when it was first introduced in the DSM-III. Nonetheless, if we were to use the current DSM-5 criteria for Gambling Disorder, Axel Freed’s behaviour in the movie would meet more or less all nine criteria, including loss chasing, preoccupation, and tolerance (his need to wager increasing sums of money to achieve the same excitement). The film refers to unsuccessful attempts to curb his gambling in the past. And as negative consequences, his actions repeatedly endanger his (academic) career and relationships with his girlfriend, mother and grandfather. However, the moral overtone of the film is that his gambling addiction reflects a failure of personal character, and an extension of his underlying depravity. This extent to which this attitude has really changed with the modern, scientific conceptualization of Gambling Disorder is, of course, a much larger question for debate.

Gabriel Brooks, Mario Ferrari & Luke Clark, 17th November 2015