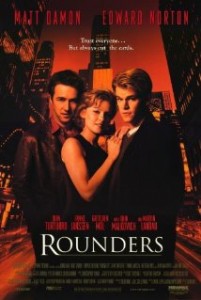

In thinking about film choices for this series, we’ve been struck that there are many films set in or around gambling establishments, but many of these films are not really about gambling. The Hangover has been suggested a couple of times –a film that has a few interesting things to say about the psychology of memory, but barely anything to say about the psychology of gambling. Rounders is a late 90s thriller about two small-time, career poker players (Matt Damon and Edward Norton, both in early roles) in New York City, and poker is very much at the forefront of this movie and central to almost every scene.

In thinking about film choices for this series, we’ve been struck that there are many films set in or around gambling establishments, but many of these films are not really about gambling. The Hangover has been suggested a couple of times –a film that has a few interesting things to say about the psychology of memory, but barely anything to say about the psychology of gambling. Rounders is a late 90s thriller about two small-time, career poker players (Matt Damon and Edward Norton, both in early roles) in New York City, and poker is very much at the forefront of this movie and central to almost every scene.

So is poker really gambling? Until recently, academic research on gambling tended to put poker to one side; it falls within sensible definitions of gambling, but the significant element of skill enables some players to turn a steady profit. Nevertheless, as we discussed in our review of 21, the variance of gambling strategies is high, and even expert poker players can be outplayed and/or unlucky. Damon’s character, Mike, is haunted by this conflict: at the start of the movie we see him quit poker after sustaining a heavy loss, but he gets drawn back in to ‘rounding’ to help long-time friend Worm (Norton) who has a debt to pay off after getting released from prison. Arguing with his girlfriend, Mike asks “Why do you think the same five guys make it to the final of the world poker series every single year? What are they, the luckiest guys in Las Vegas?” Mike’s intuition here was confirmed by a paper by Croson & Pope (2008), who found that the predictive value of past finishes was similar in world championship poker to professional golf, a game that everyone accepts is highly skilful.

The main characters in Rounders all play a serious amount of poker. John Turturro and John Malkovitch are both excellent in supporting roles, and we felt Turturro’s character was particularly realistic as the steady grafting player (“I’m not playing for the thrill of victory. I owe rent, alimony, child support. I play for money – my kids eat”). I found it curious that the Netflix description for the film labels both Mike and Worm as ‘gambling addicts’, while the Wikipedia entry calls Mike a ‘gifted’ poker player. Is there a contradiction here? The line between frequent gambling and problem gambling is often hard to draw. Certainly, we see that Mike meets several of the symptoms of problem gambling, including lying about money, jeopardising both his education and personal relationships, and ‘chasing losses’. That said, Mike’s losses arise largely from his misplaced loyalty to Worm, who compounds their problems in a series of terrible decisions (e.g. ‘base-dealing’ in a game with state troopers, who soon spot the cheat).

After parting ways with Worm, Mike recoups his debts in a tense final show-down with Teddy KGB (perhaps the nearest thing to an enduring antagonist in the film), in which Mike figures out KGB’s ‘tell’ in the way he breaks his Oreos in half. The film closes with Mike heading off to Vegas to fulfil his ambition of playing in the World Series of Poker. Lesieur (1977) pointed out that professional gambling and problem gambling do not lie at opposite ends of a spectrum; rather a professional gambler can turn into a problem gambler in a short space of time. Arthur Reber (Emeritus UBC Professor of Psychology and poker player; in attendance) has a counter-example of a degenerate problem gambler who finds success after taking up poker. But Mike’s ultimate success, and the implication that skill will eventually lead to profit, are dubious as take-home messages. Just like other forms of gambling, poker players experience cognitive distortions and often over-estimate their skill level relative to other players (e.g. Mackay et al 2014). Just because there is some stability among the best in the world, we shouldn’t infer that ‘practice makes perfect’ for ourselves.